On Christian Socialism, Sort Of

If this is your first visit here, welcome! Around two decades ago, I was a bushy-tailed Christian homeschooled high schooler who had literally never set foot in a high school classroom. (I had spent time in a junior college classroom, but that’s its own story.) My family sent me – I had the privilege to attend, rather – a two-week Evangelical summer camp focused on apologetics and keeping kids from “losing their faith” in college. If this was a serialized podcast, I’d just play a recording of this intro every time, I guess, with a cool theme song.

Anyway: I’m working my way through the pair of inch-thick notebooks from my two consecutive visits; you’re in luck, new reader, because today’s post is about a session that was entitled “A Critique of Christian Socialism”.

Not a critique of socialism; a critique of Christian socialism. Let’s dive in!

My Bona Fides

Look, I was a pretty smart kid, and I was pretty plugged into Christian culture. Our family subscribed to the Focus on the Family magazines (Clubhouse, Clubhouse Jr., Breakaway, and Brio might jog your memory if you’re from a similar background). My parents received the AFA journal, which recounted in breathless detail all of the shocking immoralities of modern culture (I’d sneak away and read it to find out what spicy things were happening on shows I’d never actually be allowed to watch – Dawson’s Creek, for example).

I read all the McGee and Me books (and later, the Wally McDoogle books). I read the Left Behind series, at least until they got too strange (I bailed at the locusts with the lion heads in Apollyon, I think.) I bought all my music at the Christian bookstore. Our family attended a small nondenominational1 church every Sunday morning, and I attended Awana every Sunday evening. (Awana is basically Christian Boy/Girl Scouts, and it’s very deserving of its own post here one day; I can still recite the pledge of allegiance to the Awana flag(!) – yeah, there’s stuff about Awana I’m sure we could unpack here – the Wikipedia article is awfully thin.)

But my family was, from my perspective, not fundamentalist. I knew kids who weren’t allowed to listen to music with drums, and families where the women only wore ankle-length dresses, and families where all the boys had buzz cuts and all the girls had braids – those were the fundamentalists. The Awana chapter I attended wasn’t for homeschoolers but instead met at the local ultraconservative college; I thought of those kids as fundamentalists.

So: while I was extremely well-versed in Evangelicalism and well-equipped to attend the summer camp I’m now writing about – even with all of those bona fides, I occasionally found myself stumbling unawares into new areas of inter-Christian conflict. This talk opens with an excellent example of that inside baseball.

Airdropped onto the Battlefield

Here’s today’s opening thesis:

Whoa, okay! This intro dropped me (and no doubt many other hapless teenagers) directly into some sort of existing conflict where guns are already blazing. “So-called Christian colleges!” Somebody named “Tony Campolo”! Something called “liberation theology” that’s a false teaching (this is a Christian phrase that hearkens to warnings against the Devil and the Antichrist and so on and so forth)! And the risk? A surrender – not to liberalism per se, not to the secularism that the speakers so far at camp have spent so much time framing as taboo, but to “some kind of religious liberalism”.

What was going on here? With the perspective of age and Wikipedia, I could now give you the short answer – the speaker was 60-odd years old, had been arguing against socialism and liberation theology for decades, and was just doing a one-hour rundown of his greatest hits for a bunch of teens. But in the moment, I was just listening to the next speaker in a long line of authoritative leaders knowledge-dump more scary stuff on us.

I’ll be honest with you: I never did get a particularly clear idea of what Liberation Theology entailed – I was left with an impression that it was some lesser corruption of true Christianity which missed the mark in some way. Like so many other topics that were introduced to us, it was really only brought up in order to teach us how to defend against it.

You, on the other hand, are free to read up on it; there’s far more to it than I am qualified to speak to here, but the one-sentence version is it’s a theological approach “emphasizing the liberation of the oppressed”. If you’ve ever heard someone say (or said yourself) that “Jesus was a socialist because he cared for the poor”, or wondered what modern conservative politics have to do with Jesus’ actual life and behavior, well, folks like this speaker spent a lifetime pushing against that idea.

Against The Oppressed

How does one manage to position themselves against the “liberation of the oppressed”? Well, here’s the next section.

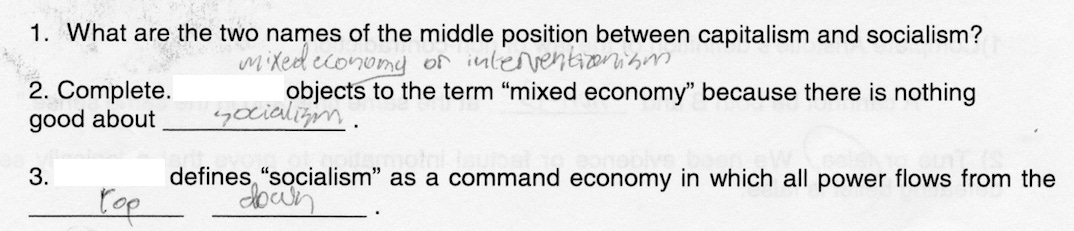

If you can’t read my handwriting: “mixed economy or interventionism” is the term of the “middle position” between capitalism and socialism. [Redacted speaker] objects to the term because there’s “nothing good about socialism”. And he defines socialism as a “command economy in which all power flows from the top down.” (What power, and what top, are questions a touch nuanced for a 1-hour presentation that has a lot to cover.)

It’s cool, I’ve got an illustration for you in the margins. Easy!

And so forth:

Your head might already be spinning if you were equipped at any point in your life with more nuanced definitions of socialism and capitalism, or don’t see them as the only two points on an axis, or are wondering how well or often capitalism prohibits acts of force, fraud, and theft, or who is expected to prohibit them, or why capitalism would even be incentivized to do so, or …

This section interests me, in retrospect, because believing that unless you accept Jesus into your heart, you’ll be sent to an afterlife of eternal punishment sounds an awful lot like a “violent means of exchange”2. I think the speaker meant it to frame socialism (or, broadly, government regulation) as punitive, compared to market forces as incentivizing a shared good.

Capitalism neutralizes greed! To a teenager with zero other points of interaction with this material, hearing from a speaker behind a pulpit at a special camp they were privileged to attend, this landed completely, confirming my underdeveloped priors and setting me up to reject not just socialism but anything that hints at socialism.

Why not? If I make a better sandwich than my neighbor, should that not drive them to make a better sandwich at their restaurant? Is this not simply a positive-sum game? Do not all households own microwaves? Does the rising tide of American prosperity not lift all boats?3

My page of notes wraps up with these 3 bullet points.

Christians ought to care about social issues

That concern must be linked to sound thinking

Things are not always as they seem

Let’s unpack these.

1. Christians ought to care about social issues

This first bullet is a generalized “we’re not the bad guys” defense – we’re not talking about ignoring the oppressed, for of course we should care about the oppressed! If you’re asserting viewpoints like this, you have to define the playing field immediately, lest the conversation be about the idea that you don’t care about social issues. Another way to read this 3-bullet list is in a cumulative sense: given that Christians ought to care about social issues, that concern must be linked to sound thinking.

2. That concern must be linked to sound thinking

Christians as a whole (remember, this is nominally focused on refuting “Christian Socialism”) should care about the oppressed; the speaker isn’t trying to say that Chrstian Socialists aren’t doing that. Instead, he’s arguing that the thinking of how to care about the oppressed is simply unsound.

For the Evangelical mindset, there are two key aspects undergirding this one line. At a basic, more practical, and not explicitly religious level, the tone here hearkens to previous days’ assertions that Evangelicalism is inherently reasonable – it’s not just not irrational, but is the most rational worldview. Evangelicals, and conservatives more broadly as a whole, hold to the idea that capitalism is more fair and balanced. In other words, that it’s based in sound thinking.

The left, on the other hand, is often framed as naive at best. The left is using Big Government to manhandle the free market; the left doesn’t understand what’s really going on; of course we should help the oppressed, but if we just give them money they’ll become lazy … bog-standard conservative stuff. (Of course, this mindset can and does metastasize into criminalizing the oppressed (minorities, immigrants, the poor) but in this particular vein, let’s work within the positive light the speaker is attempting to shed on the evangelical conservative approach to social issues.)

The other aspect that’s at play here is one that spans ideology, worldview, religion, the whole gamut: the idea that tasking the government to care for people is an attempt to solve a God-level problem (the sinfulness of mankind & the fallen state of the world) without God. This is where the contrast of capitalism vs. socialism starts to blur together with the contrast of theism vs. secularism. Unless an evangelical has crossed the line into open Christian nationalism, they will generally say that this is a nation founded on “Judeo-Christian”4 values (and argue that our prosperity comes from our foundation in said values), but they stop short of saying that the nation itself is Christian. Additionally, modern evangelicals largely believe in some form of apocalyptic End Times / Rapture theology, and as such, do not believe in social progress. The goal is not to save the world, but to save souls from a world that is beyond saving.

So, there is a very real fatalist streak to the evangelical when it comes to examining social policies, that’s grounded in a fear of some slurry of socialism, communism, Marxism, secularism, and general godlessness. The efficacy of a social policy, then, ends up being beside the point, because it’s coming from a place of secular motivation.

Ultimately, evangelicals believe that suffering and persecution is to be expected, given that the world is fallen and the literal (but temporary, until Christ’s return) domain of Satan. So, if tragedy or injustice takes place – even large-scale, systemic tragedy – there’s always opportunity to tell oneself it’s “a symptom of a broken world”, or more broadly, “God’s unknowable plan”. When that mentality intertwines, as it does very often in the US, with the capitalist notion that distributing resources equitably is unfair to market forces or what have you, and you end up with a whole lot of reasons to reject progressive social policies, even when the cause & effect of those policies seem obvious.

3. Things are not always what they seem

And finally, a wide-open door: things are not always as they seem. Jesus would be a socialist, you say? Well, it’s not all that simple, comes the evangelical’s answer. That was a different time, in key ways that the I don’t necessarily have to specify – just gesture towards in order to dismiss the concept. Christians should help the poor? “Things aren’t always what they seem” is an incredible counterspell to Occam’s Razor, allowing seemingly-simple arguments to bounce off purely due to their simplicity. You’ll never corner an evangelical with a silver-bullet statement because they’re equipped not only with a different set of concepts & definitions, but with a reflexive rejection of any opposing view’s apparent face value.

Whew. Next time we’re doing creationism, so hang on tight and I’ll see you in a couple of weeks.

This is technically untrue; our church was “Evangelical Free”, but throughout my childhood I and others referred to it as nondenominational. Evangelical Free Church of America is actually indeed very much a denomination, and is also not “evangelical-free”, two facts I had wrong for the majority of my life.

This observation isn’t some sort of smoking gun, of course; an evangelical also believes that your sinful state does sadden God, but it also isn’t his ‘fault’ per se. While he is omnipotent, sinfulness is simply against God’s nature as perfectly good; he can provide you a door to walk through to escape your fate, but it’s up to you to walk through it; it’s really on you, not him, to avoid damnation. (You can spend some time trying to mentally unpack the upside-down-and-backwards power dynamics of that relationship, if you like.)

I often debate who my intended audience is with this blog – ex-evangelicals, people with no evangelical background who are baffled by the American Right, evangelicals who are feeling uncomfortable and starting to wonder how it’s come to this, and so forth. Ultimately I try to write in a way that is empathetic and draws in all but the most looking-for-a-fight readers. However, I’m just not going to spend much time trying to debunk (or bunk) the pros and cons of capitalism; this blog is about how this information was presented at the time, and if you have countervailing viewpoints on this speaker’s framing of capitalism and my pretty curt rejection of it, I’m afraid this blog just isn’t going to stop off at that exit.

As an adult, I’ve learned this is not a commonly-used term outside of Evangelical circles, especially in this context. When evangelicals say “Judeo-Christian”, they’re gesturing widely at the cumulative moral & ethical body of guidelines present in the Old & New Testament together. (I think they do it because it sounds more official and studious than simply “Christian values”.) Wikipedia informatively provides that the first person to use this term in this sense is George Orwell(!) and it became popularized as a sort of overlap with Christian Zionism in the early 20th century. For more on this viewpoint, you can read up on the theology of Supersessionism.